How Will Brands and Information Shift in Agriculture Across Time?

(~13 min read) Consumer value towards brands are a moving target. See what ag brands can learn from our most beloved consumer brands and how distribution of those brands may change...

Welcome to this month’s Deep Dive. Today, we’ll be exploring how brand values evolve and the way content creation is changing marketing and distribution. In addition to the monthly Deep Dive, stay tuned for the weekly Agriculture’s Honest “Take 5” where we break down and review five important pieces of curated content. Now, on to the Deep Dive!

For those who can only spare a minute, here’s the TL;DR…

Everything has a brand attached to it, for good or bad. While trends dictate brand value in the short-term, technological advancements dictate brand value in the long-term

Platforms and technology augment a consumer’s experience, making digital enablement a key driver to human brand interaction with time. This augmentation draws us to value digital platforms at the top of our list

A farmer’s role through digital augmentation may disrupt the ag industry’s most legacy brands, shifting brand value to entirely new enterprises

Utilizing content creation and influencer strategies has become key for low-friction distribution, particularly in consumer goods. Though there’s nuance, agriculture can use these strategies to augment and amplify their brands

BRANDS UNDERGO STRUCTURAL EVOLUTION

Brands are astounding. People, products, and companies each carry one for good or bad. Humans are malleable and our perceptions of a brand can change quickly. Enabled by mobile connectivity, social apps have distorted our dopamine and discipline with distractions and alter egos. In real-time, everyone can learn what’s hot and what’s not. The result is a culture centered around the theme of “the current thing”.

Like it or not, brands are powerful. Unfortunately, the most common brands do not always equal the best products. For this reason, I’ve always had some loathe for companies that focus more resources on brand strategy vs. truly creating valuable things. Nonetheless, as consumers, we have the ability to vote with our wallets and can only blame ourselves in these situations.

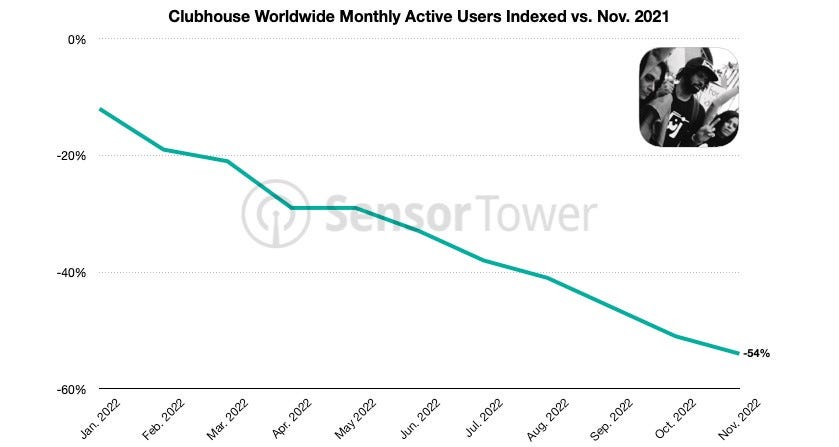

Brands can go both ways in momentum. Some are like fine wine and only get better with time. On the other hand, with enough time, some revert to the mean as hype wears off and is left with the likes of Clubhouse and other trendy short-lived brands that consumers mistake for spam.

I like to think of brand evolution through the lens of short-term and long-term. In the short-term, a brand is dictated by culture and trends. In the long-term, it’s more structural through the development of new technologies and business models.

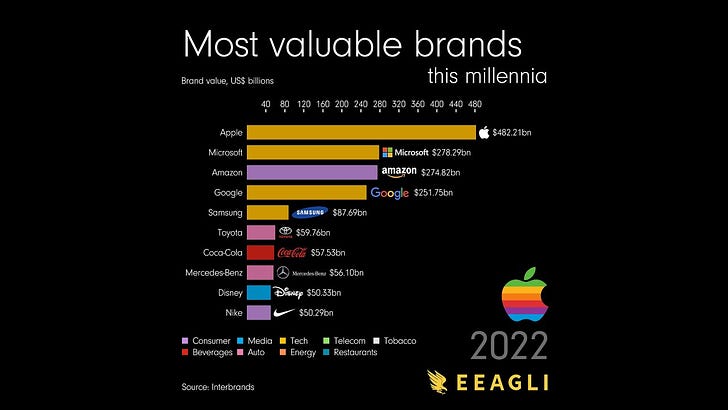

The video below shows a time-lapse of changes to the most valuable brands. One can argue the quantification and ranking of “most valuable”, but the point is clear. In past decades as tech products became accessible to average consumers, the brand value of those companies outperformed the most iconic consumer brands we know and love.

Watch the change of the most valuable brands from 2000 to 2022:

This is not a shocking discovery as human consumption habits have entirely evolved over the past decades. Instead of continuous interaction with physical products, the rise of allocation to intangible information has gnawed into a human’s market share of attention span and interaction. To quantify this:

The average person spends 3 hours and 15 minutes per day on their phone, checking it an average of 58 times

Google processes ~8.5 billion searches per day, up from just 10,000 in 1998

E-commerce has gone from nothing to 15% of addressable retail in 2 decades

These interactions with the brand are very different experiences from what we see with physical legacy brands. Even though Coca-Cola sells 1.9 billion servings of drinks daily and Nike sells 780+ million pairs of shoes each year, they sit at a fraction of the brand value of tech behemoths. Why is this?

I believe a possible answer to the evolution of brand value is the combination of a great product matched with a great user experience. A similarity among these top tech brands today is that they’re better associated with platform technology versus just products. An iPhone is most certainly a product, but it behaves as a platform for other brands’ distribution and establishes endless functionality for users. Similarly, the product of Google Search provides directed answers to sources in a seamless way without friction. The product strategy for most of these companies aligns with aggregation theory in which there’s a very direct relationship with users in a zero-marginal cost structure.

A product-only brand doesn’t offer a platform experience and thus has a more difficult time bringing out a gratifying user experience. For example, a Patagonia sweater is a great product that can make someone feel proud to wear. However, the tangibility of the product has difficulty offering constant interaction and the same experience as scrolling through Netflix movie options.

For many of these household societal brands, it is less about being disrupted from within the industry and more about seeing disruption from outside the industry. It’s not that Nike or Coca-Cola have fundamentally lost their edge to Under Armour or Pepsi, but to totally unrelated market categories. This is why in the long run, brands are much more susceptible to structural technical evolution than anything else.

THE STRONGHOLD OF AGRIBUSINESS BRANDS

It’s relevant to think of these principles with respect to agriculture. In the industry, brands are incredibly strong. If I had a dollar for every time I hear the questions…

“Is your farm red or green?”

“What’s your favorite soybean seed?”

Rural communities are a small world and word travels fast. Brands that strike positivity from customers will gain momentum quickly. It’s for this reason that agribusiness is notorious for giving out apparel. Happy customers are proud to represent.

Agribusiness brands have always been about machinery, seed, chemical, and their retailers. Unlike fertilizer or fuel, these products have a critical mission to push brand differentiation as a strategy. If a business can prove product quality, the customer lifetime value can be high. For input products, the complexity of learning new systems (germplasm and traits, historical trials, application requirements, etc.) allows for high switching costs once trust is ensured. This makeup has been a major advantage for legacy companies within the industry.

The connectivity for farmers to their brands makes sense. Almost 100% of their day involves interaction with the products and the people selling those products and services. If they aren’t working with (or in) those brands, they’re likely being pitched them. Note that historically, these interactions have always been about the tangible realm. However, using the analogy we see with consumer brands, can new technology and business models shift the brand value in agriculture?

HOW CAN AGRIBUSINESS BRANDS EVOLVE?

Fast forward a decade from now and it’s hard to imagine agriculture the same way it is today. Edge computing and machine learning have gotten to a place where automation and prescriptive recommendations will be very real in the 2030s. If we assume those structural changes augment a farmer’s role, how do the brand interactions correspond?

As an exercise, let’s assume that the average farmer today allocates 90% of their time to tangible farm tasks (operating machines, etc.) and 10% of their time to software tools. By default, with this much of an allocation delta, a farmer will be much more receptive to the brand value received in that 90% of interactions.

In the next part of this exercise, assume the allocation transitions to a 50/50 split for time. In this world, a farmer is spending 50% of their time interacting with software. This may come in the form of farm management, machine control, virtual agronomy, product research, and other tasks. In this scenario, the farmer’s work is augmented with an entirely different set of products and tools as in the 90/10 case.

If we compare the physical to non-physical interactions we’ve experienced as consumers in the past 20 years and the brand value evolution over that time, it’s reasonable to assume that farmers will prioritize software-enabled brands versus the popularized brands today.

Place yourself in the year 2035. For a software tool that integrates the control and actuation of any farm equipment brand, is it the software or the actual farm equipment brand that is most appreciated? My guess is it’s the software. Similar to platform aggregator brands recognized earlier, a farmer’s majority of time is spent working within that software vs. in the actual equipment. When they close their laptop for the evening, they’ll be delighted with their experience operating within the software platform and less so on the controlled equipment.

This is just an example of how the brand value could evolve within agriculture. With the average farmer age of ~60, this point of view likely doesn’t become reality within the decade. However, as the next generation who’s spent most of their maturing life in the digital world, this scenario is highly realistic.

…ENTER CONTENT CREATION

Of course with brand evolution, a viable distribution strategy is required. This is especially true in an industry so locked into legacy brands. Stealing from the consumer world, can content creation be a paramount strategy in developing brand evolution in ag?

Starting consumer companies have become easy. Today, there’s essentially an outsourced company for everything (e.g. Stripe for payments, Squarespace for websites, Figma for design, etc.) which has made the barriers to entry very low. This ease has led to brand management being the sole differentiator. As a result, there’s been a boom in talent and an entire economic category dedicated to content creation that supports brands.

Many companies now have internal content creation strategies that include newsletters, podcasts, conferences, and other forms. In addition to their own, leveraging “influencers” across target markets have become another effective strategy to amplify brands.

This content (internal and external) has become the gas behind distribution strategies. In a world that is crowded with ads and marketing fluff, it’s hard for consumers to distinguish useful from useless. This is why “influencer culture” has been an effective point for distribution. With the democratization of personalities (Joe Rogan, Lex Fridman, etc.) through direct-to-consumer media channels, followers are able to attribute trust to those personality brands. For example, if people correlate Joe Rogan with authenticity, trustworthiness, and health, an endorsement for Athletic Greens lowers the friction to purchase as Rogan’s credibility is linked to the product.

This trend among generic consumer goods prompts the comparison among agricultural products. To bring this idea to life, I’ll introduce the YouTube channel, bigtractorpower. The content creators describe the channel in the following way:

Big Tractor Power is dedicated to sharing farm machinery in action. Tractors, combines, implements and all things related to farm equipment are our focus. Our videos range from the newest machines on the market to the great classic iron of the 20th Century.

Established in 2010, bigtractorpower has 400,000 subscribers and 240 million cumulative views since its founding. Compare this to the dominant equipment manufacturers John Deere and CNHI. These two represent $150+ billion in market cap and over 50% market share. Yet, the two combine for just ~300,000 subscribers, 25% less than the personal YouTube channel of bigtractorpower.

bigtractorpower has created differentiated content that people appreciate and value. By doing this for 13 years, they’ve generated a trusted relationship that followers can relate to and uphold. Other content creators like Hudson’s Playground (1.36 million subscribers) or Millennial Farmer (999,000 subscribers) have accumulated massive followings, hungry for unique content.

What these creators have unveiled is the utilization of today’s modern platforms to tap into sub-cultures that were previously hidden from the world. YouTube, Substack, Facebook groups, and others allow content to be delivered to very specific niches that couldn’t be discovered without direct-to-consumer models.

CAN CONTENT CREATION WORK IN AGRICULTURE?

It’s clear that content has been a viable business strategy for influencer roles. For example, the YouTube star, MrBeast, resourcefully used his universal 135 million subscribers to launch other businesses like a burger chain and chocolate bar brand. This is an example of a recently discovered playbook that places the influencer and content creation strategy as the engine for distribution. While it has been proven successful in direct-to-consumer products, we all know that agricultural distribution is an entirely different game.

Referring back to some of the ag YouTuber channels mentioned previously, how can they have a role in something like this? I can see a world in which trusted influencers carry an accelerated pathway to product adoption. Assuming a given influencer is known as an authentic and sensible farmer, a product endorsement from them would go a long way in driving adoption for like-minded followers.

I’m a strong believer that utilizing an existing distribution channel in agriculture is critical for product adoption. Farmers do not have enough time to evaluate and test the many products that come our way. Agronomists and advisors serve as technology aggregators that limit the complexity and labor required for farmers. They are localized influencers. With this in mind, there’s no reason why this same mindset cannot be supplemented through digital influencers that have zero marginal cost of advertising. The combination of physical and digital influencers can combine to be an augmented distribution point. As David Friedberg states:

“Distribution is the number one problem for consumer goods and services. If you don’t naturally have content creation in your blood, you will have to go and buy a content business or you will not be able to compete effectively.”

Trung Phan eloquently hits on the above statement perfectly:

Why? Because consumer goods are so competitive — and so easily substituted in many cases — that the best way to stand out is with story and content. And social platforms like Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok are where people are increasingly going to consume said content.

Traditional consumer brands without a successful content play are stuck spending huge dollars on advertising. In fact, Procter & Gamble is the world’s largest advertiser, spending $11.5 billion in the 2021 fiscal year.

MrBeast can sidestep such ad spending because he already commands the attention of millions. MrBeast of course has expenses. Any ad money he makes from YouTube gets plowed back into the business at the current pace of $8 million a month.

Here’s a key difference, though: Advertising a product may create short-term interest, whereas making content creates an owned asset that can continually bring in new fans.

If one applies this thought-provoking strategy to agriculture companies, it’s not unacceptable to hypothesize that a large retailer like Nutrien or Wilbur Ellis would fit this model perfectly. Aside from internal content creation, they could utilize their farmer network to promote and influence branded products or acquire and advertise with existing content creators.

There’s no doubt a strategy as such would be hard to pull off for a complex system like agriculture. There’s very low risk in buying an endorsed consumer product from a trusted influencer vs. an expensive product put towards your livelihood. However, one can sketch out a path to how content creation can augment the distribution and omnichannel experience for the ag industry.

With that, it’ll be interesting to see how the next generation of farmers changes this and how brands evolve to keep relevance with the changing technical structures that are to take place in coming years. To that extent, I look forward to participating in it.