Agriculture's Honest "Take 5" Weekly Roundup: 03/03/23

(~10 min read) China's GMO conundrum, food waste, competitive advantages, and more...

Welcome to this week’s Agriculture’s Honest “Take 5” roundup where we break down five curated pieces of industry content. Stay tuned for this month’s deep-dive post where we evaluate a specific industry topic. Now, on to the Takes!

TAKE 1: “China must befriend GMOs, and fast”

China’s food security has been a top priority and concern of Chinese officials for the better part of two decades. Just as the Western world has become too comfortable with the outsourced manufacturing of critical goods, China has also become a fragile victim of Maslow’s most basic need…FOOD!

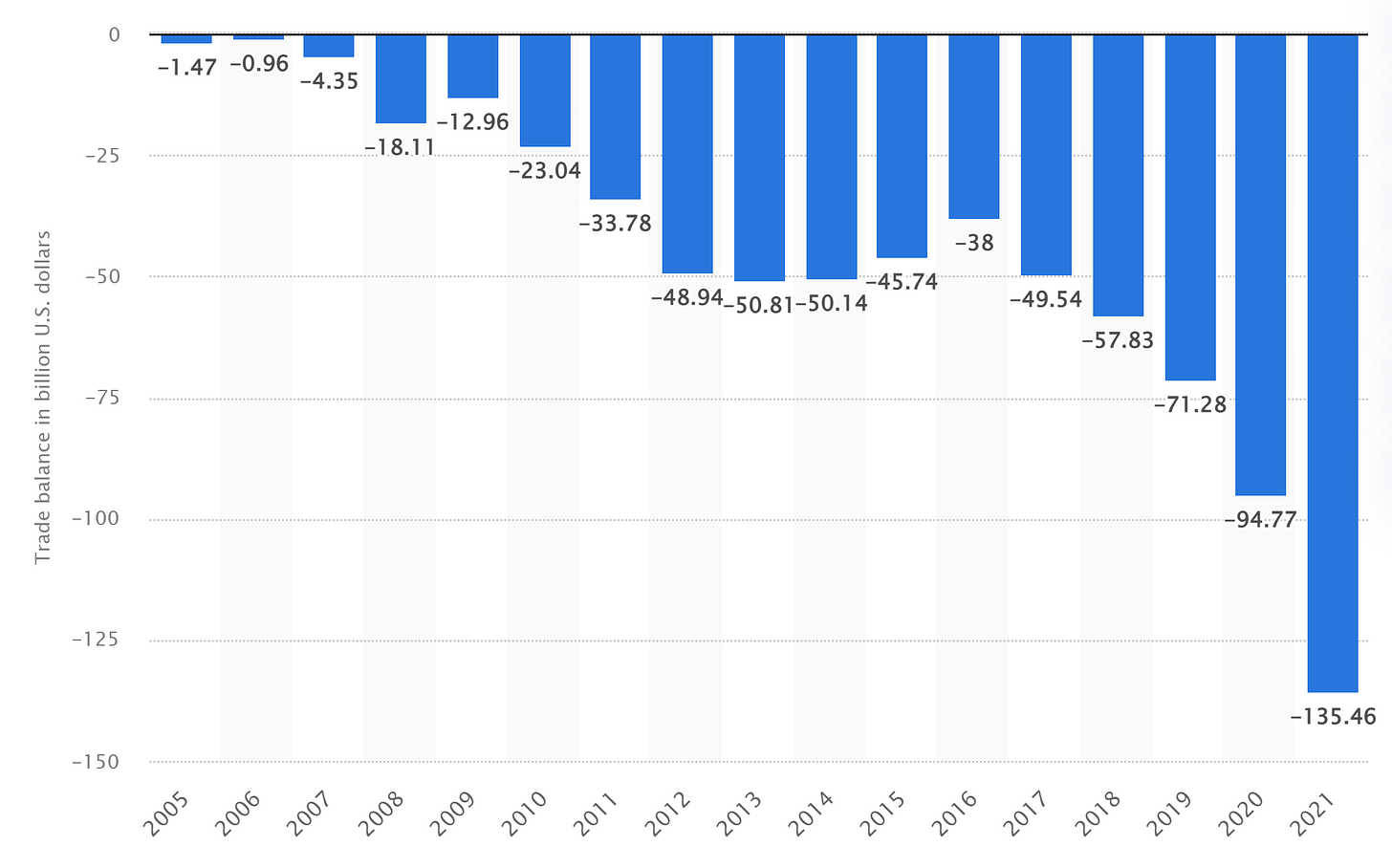

China's trade balance of agricultural products:

Similar to how the US has a difficult time competing with manufactured goods, China has a hard time competing with farm productivity where yields are 60% less and the cost is ~1.3x higher than that of the United States.

While China has the desire to diminish reliance on food imports, Foreign Policy makes an interesting argument on the rising issue of Chinese farmland:

China has experienced alarming levels of farmland loss and deterioration in recent years. The most recent land use survey showed that China’s total arable land decreased from 334 million acres in 2013 to 316 million acres in 2019, a loss of more than 5 percent in just six years. Shockingly, more than one-third of China’s remaining arable land (660 million mu, a traditional unit of land measurement in China and equal to roughly 109 million acres, slightly larger than Montana) suffers from problems of degradation, acidification, and salinization.

The land has been eroding faster in recent years. The annual net decrease of arable land has risen from about 6 million mu (about 988,421 acres) from 1957 to 1996 to more than 11 million mu (about 1.8 million acres) from 2009 to 2019. This means that between 2009 and 2019, China lost farmland equal to about the size of South Carolina. China’s diminishing farmland is also losing productivity due to over-cultivation and excess use of fertilizers. China’s fertilizer usage in 2018 was 6.4 times that of 1978, but grain yield in 2018 was only 2.2 times that of 1978.

Aside from the deterioration of high-quality farmland, increased urbanization is expected to eliminate another ~3.5 million acres over the next few years. These coupling factors are the reason why China looks to take further control over farmland. In 2022, the State Administration for Market Regulation and the Standardization Administration of China set criteria for the increased investment and development of nearly 200 million high-quality farmland acres across varying Chinese regions. Of course, if you cannot properly perfect it internally, the obvious strategy is to purchase internationally. As many likely know, this has been something China has been carrying out (though still minuscule today).

While the preservation of good farmland makes sense, the real answer lies in GMOs and the increased productivity of using them. Despite cotton and papaya being predominant GM crops, China has been slow to accept GMOs at scale. While China seems to be coming around to them, the progress remains modest. According to a recent Reuters article, China’s ministry will authorize the use of GM corn on <1% of expected corn acres. For a country that imports 20 million tons of corn, these acres are meaningless.

In a world where increased ag resiliency and farmland preservation are so important to China, why is there so much hesitation for GMOs? While public opposition is often cited, some things just don’t add up. To start, cotton and papaya production is already GMO-dominant. Additionally, the vast majority of corn and soy imports from the US and other countries are from GMOs. Most interestingly, China’s breadbasket regions have been cited as illegally planting GM crops (samples show 93% of fields). The likely reason comes down to most GM technology being held by the Western world. As China is often too proud to utilize ex-China technology, GMOs are no different. The reality is that China will need to get over this if they actually want to make an effort in increased food resiliency. Otherwise, the US and Brazil can probably expect a continued flow of strong exports for some time.

TAKE 2: “Taking ownership of the food waste problem”

Food waste across the supply chain is a highly inefficient dynamic with 30-40% of the food supply wasted annually. Food waste is something that everyone morally hates. Not to mention it’s a huge sunk cost as tons of input and productivity went into a product so close to final consumption.

Despite all this sensible hate for food waste, there are weird incentive structures that exist. The farm gate and manufacturers actually benefit from this as it’s an additional ~30% of artificial demand. Additionally, manufacturers have a lot of brand value to lose if their product isn’t at peak freshness. For this reason, “best before” or “sell-buy”, among other phrases, are clever labels meant to encourage consumers to not eat past the date. The catch is this date doesn’t necessarily equate to when the food is actually bad. Because of this psychological role in labeling, 7% of food waste is because of date marking.

This week, Apeel announced a new preservation coating for mini-cucumbers. Apeel is a food preservation company with a botanical coating for produce peeling. The coating is designed to slow the rate of water loss and oxidation, allowing fresh produce to stay fresh longer. With biological coatings for 9 different fruit and vegetable types, Apeel is trying to dent the economics of food waste. By partnering with suppliers and retailers, Apeel can increase the profit for their retailer network, the common losers in the food waste equation.

Through Apeel’s beachhead coating technology, the late-stage startup has also added incremental technologies to support food waste for retail. For example, Apeel supports its retail network with analytics around inventory management, market research, branding, and quality control. While this expansion strategy doesn’t focus on economies of scale for a specific product, it’s a classic “jobs to be done” blueprint. With retailers suffering huge food waste losses, their job request becomes “take care of my food waste problem”. Through the incorporation of varying technologies, Apeel can fulfill that job as they position themselves as the ultimate food waste solution. While a product portfolio of biological coatings, data analytics, and consultation don’t appear synergistic in product development, it’s evident in other ways. The ability to carve out a critical piece of the supply chain and add new services with difficult-to-acquire customers makes this strategy a homerun. Building this kind of expertise across multiple facets allows Apeel to become a key partner for the lifetime of the retailer. Not to mention, they’re providing a great service to the global problem of food waste. Go Apeel!

TAKE 3: “Productivity as a competitive advantage”

Janette Barnard of

featured a great writeup on Bayer’s new breeding facility and what it means for a P&L statement. To her point, it’s a combination of various technologies (gene sequencing, machine vision, etc.) coming together to form a dynamic tech stack that results in increased revenue or lower cost structures (sometimes both).Internal tech stacks can most certainly provide lifts in revenue opportunities. However, my interest often lies in productivity improvements for a workforce. While it’s not commonly referred to as a competitive advantage, internal productivity can be a less tangible moat that separates a company from the competition. By using tools to make teams more efficient, there are cascading positive effects that include low employee attrition, rapid product iterations, and improved cost structures. Simply stated, if a company’s team is 20% more productive than a peer, this is similar to either a 20% lower salary budget or a 20% increase in headcount. This can result in cheaper products, better service, or higher margins, all things that begin to build an advantage around a company.

Productivity tools within a flat organization are what often gives startups a huge edge over their larger competition. Startups are much quicker in implementing productivity boosters and enabling the latest technology to allow them to iterate faster. Since the workforce tends to be younger, there’s better awareness of the most recent tech stack features that can be implemented for improved workflow. Think Canva over Adobe (design), HubSpot over Excel (CRM), and Notion over MS Office (IoT workplace)…just to name a few examples. Starting fresh with internal productivity software and practices vs. integrating these at a later date and re-teaching the workforce how to implement the tools offers a significant time gap (if those companies even migrate to modern tools).

While I agree with both sides of the Buffett vs. Elon debate on competitive advantages, there’s a nuanced point in which sustaining a competitive moat must include a culture of quick iterative innovation. A tech stack that enables productivity gains can be one of these advantages if it’s sustained.

TAKE 4: “Vertical farms are in the trough of disillusionment”

If anyone is interested in learning the latest woes of vertical farming, Fast Company wrote a very bearish article on the emerging industry. While I’m happy to admit my confidence in the industry long term, the reality is this article is spot on. Earlier this month, I wrote about the similar distress the industry faces. Commodity producers that act and spend as if they’re tech companies will not carry out a practice that induces a return on invested capital.

Just as there is for outdoor production, there must be a bifurcation between producers and tech providers. An Iowa row crop farmer would not spend tens of millions to develop proprietary technology that can only be used on their farm to produce corn and soy. The business models, employee culture, and core competencies just don’t match mix well. Producing an undifferentiated commodity is very different than developing technology infrastructure. The strategic framework and return on capital for those propositions are day and night. To hit this point home, I’ll recommend a great analogy that Jeff Bezos has used:

Jeff uses this analogy for AWS. He talks about European beer breweries around the turn of the 20th century.

Electricity has just been invented. This was this massive enabling technology. Breweries could now brew vastly more quantities of beer than you could before electricity.

The first breweries to adopt it built their own power generators. It worked fine for a few years but it was super capital intensive.

Then the utilities companies came along and the next generation of breweries just rented the power from the utilities companies.

[They beat] the first generation of breweries because guess what: whoever makes your electricity has no impact on how your beer tastes.

Jeff’s argument to all of these startups [at YC] was focus on what makes your beer taste better.

There’s two lessons here. One, which is what he’s arguing - you should focus on the attributes of your product that your customers are going to care about.

The second, if you look what Bezos did, not what he said, is that being a utility company is an exceedingly great business. Particularly, being an unregulated utility company.

It can be so defensible and powerful. If you can be a mission critical piece of infrastructure that other companies can use that they need, but doesn’t actually make their beer taste better, it’s a great place to be.

In all, I’d highly advise any companies that try to attempt both, to rethink their goals and strengths/weaknesses. Sure, just growing leafy greens isn’t that sexy, but it can be profitable!

TAKE 5: “Brand evolution”

This week was my first monthly Deep Dive post where I discussed brand evolution. An interesting takeaway from watching consumer value towards brands over decades is that in the short term, brands are often dictated by trends. However, in the long term, they’re dictated by technology shifts.

In the past 20 years, it’s clear that tech platforms (Apple, Amazon, Google, etc.) have become our most valued brands in exchange for physical products (Coke, Nike, etc.).

Watch the change of the most valuable brands from 2000 to 2022:

Ag brands are quite strong with farmers. However, given the changes seen in consumer brand value, it’s fair to assume that a farmer’s value toward brands will change as the role is augmented with increased digitization and automation. Will the workflow automation software have higher brand value than the machinery itself?

Supplemented with that, I discuss how content creation and “influencers” have a role in the distribution and marketing of products. Ag retailers are basically local influences. However, creating an omnichannel presence for them to interact with will be key.